On December 10, 2025, the General Court delivered the latest judgment in the long-running Intel saga.[1] The General Court upheld the Commission’s 2023 decision to fine Intel for abusing its dominant position in the market for x86 central processing units (“CPUs”) between October 2002 and December 2007 through ‘naked restrictions,’[2] but reduced Intel’s fine from €376 million to €237 million to reflect the “temporal and material scope of the infringement”.

Background

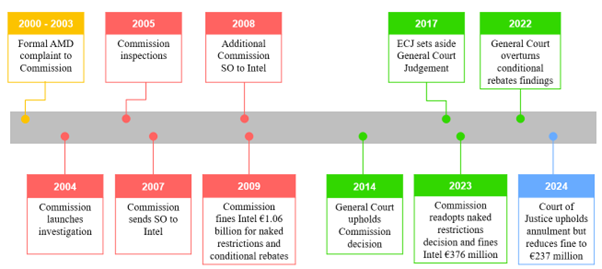

2004. The Commission initiated an investigation against Intel following complaints from AMD, Intel’s competitor in the supply of x86 CPUs.

2009. On May 13, 2009, the Commission imposed a €1.06 billion fine on Intel for abusing its dominant position in the worldwide market for x86 CPUs, where Intel had a market share of c. 70%. The Commission’s finding was based on Intel’s exclusionary measures, including (i) conditional rebates and (ii) three naked restrictions (i.e., payments made to original equipment manufacturers (“OEMs”) on the condition that they limit, delay or in some other way restrict the commercialization of certain AMD-based products).

2014. Intel appealed the Commission’s decision to the General Court, alleging that the Commission had failed to demonstrate, through its as-efficient-competitor (“AEC”) test, that Intel’s rebates were capable of foreclosing equally efficient competitors. The General Court dismissed Intel’s appeal in its entirety without examining the Commission’s application of the AEC test, instead relying on the legal standard established in Hoffmann-La Roche in 1979.[3]

2017. Intel appealed to the Court of Justice, which ruled that exclusivity rebates by dominant companies are presumptively but not per se illegal under Article 102 TFEU.[4] The Court of Justice set aside the General Court’s 2014 Judgment and remitted the case, holding that the General Court had erred by failing to review the Commission’s effects analysis.

2022. On remittal, the General Court annulled the Commission’s €1.06 billion fine, marking a shift from formalism to effects-based analysis under Article 102 TFEU.[5] The General Court held that the Commission erred in treating exclusivity rebates as inherently abusive without assessing actual effects, and that the Commission’s AEC tests were flawed and failed to properly evaluate market coverage and the duration of the conduct. Whilst the General Court upheld the Commission’s findings on naked restrictions, it annulled the fine in its entirety because neither the Commission nor the General Court could isolate the portion of the fine attributable solely to those naked restrictions.

2023. On September 22, 2023, the Commission readopted its infringement decision insofar as it concerned the three naked restrictions, with a €376 million fine to reflect the narrower conduct scope.[6]

2024. On October 24, 2024, the Court of Justice upheld the General Court’s annulment of the 2009 Commission Decision, reaffirming the requirement for a proper effects-based assessment of Intel’s rebate practices while referring limited residual issues back to the General Court.[7]

The 2025 General Court Judgment

Intel had sought an annulment of the contested decision, arguing that: (1) the Commission ought to have verified whether it had the jurisdiction to make findings in relation to the restrictions imposed on Acer and Lenovo; (2) the contested decision required a new, more detailed Statement of Objections (“SO”); and (3) the level of the fine was disproportionate and unlawful.

The Commission has jurisdiction to reimpose a fine for a previously established infringement

First, the General Court held that the Commission did not need to re-establish its jurisdiction to adopt the findings under review. Those findings were based on the three courses of conduct which formed the basis of the part of the 2009 Decision that had not been annulled.[8] Both the infringement findings and the Commission’s jurisdiction to make them had become final when Intel failed to appeal the General Court’s affirmation of those findings in the 2022 Judgment.[9] There was therefore no new finding of an infringement: the Commission was merely complying with the 2022 Judgment in resetting the amount of the fine.[10]

The Commission does not have to issue a new SO where there is no new infringement

Second, the General Court confirmed that the Commission was entitled—and required—to rely on the part of the 2009 Decision that had not been annulled.[11] Contrary to Intel’s submissions, no new SO was warranted.[12] For the same reasons, the General Court found that the contested decision was adequately reasoned, as the relevant context arising from the 2009 Decision “was known to the applicant”.[13] Lastly, the General Court held that Intel’s rights of defense and in particular, its right to be heard, were not infringed by this procedure, as the contested decision was based on a prior finding of single, continuous infringement.[14]

The Court’s jurisdiction to alter a lawful and proportionate fine

Third, the General Court rejected Intel’s arguments seeking an annulment of the fine, holding that the amount set by the Commission was neither disproportionate nor unlawful.[15] The General Court nevertheless exercised its unlimited jurisdiction under Article 261 TFEU and Article 31 of Regulation No 1/2003–which provide that the Court may review the legality of fines and may cancel, reduce or increase them–to substitute its own assessment for that of the Commission in determining the level of the fine.[16] While emphasizing that the 2023 Decision was lawful and proportionate, the General Court held, that it was “possible, fair and appropriate to take account of other parameters, relating to both the duration of the infringement and its gravity… in order that [the fine] be set with increased precision”.[17] The General Court thus decided that, where several lawful parameters are available, it must select the one that “sets the amount with the greatest relevance”.[18]

The General Court relied on two factors in assessing the proportionality of the fine in this regard. First, it found that the Commission had not sufficiently taken into account the 12-month gap separating the naked restrictions imposed on HP from those applied to Lenovo.[19] While the General Court identified this temporal discontinuity as relevant to the assessment of the scope and gravity of the infringement, it did not expressly discuss how that omission affected the calculation of the fine or quantified the impact of the gap. [20] Second, although accepting that the Commission was in principle entitled to use all EEA sales of x86 CPUs in 2006 as the reference point, the General Court attached particular weight to the limited material scope of the infringement. [21] It noted that the naked restrictions covered only 8.2% of the units concerned.[22] In the General Court’s view, this revealed a disconnect between the breadth of the sales base used for the fine calculation and the economic reality of the conduct, which was confined to a narrow subset of Intel’s overall x86 CPU sales.[23] On this basis, the General Court exercised its unlimited jurisdiction and reduced the fine by 37%, rather than conducting a factor-by-factor fine recalculation.[24]

Key takeaways

With this Judgment, the General Court reaffirmed its unlimited jurisdiction to alter a fine imposed by the Commission. In exercising that jurisdiction, the General Court is not bound by the Commission’s fining guidelines, but is instead guided by the broader qualitative considerations of temporal and material scope of the infringement.

[1] Intel Corporation v. Commission (Case T-1129/23) EU:T:2025:1091 (“2025 Judgment”).

[2] Intel (Case COMP/C-3/37.990), Commission decision of May 13, 2009 (“2009 Decision”).

[3] Intel Corporation v. Commission (Case T-286/09) EU:T:2014:547 (“2014 Judgment”). See also Hoffmann-La Roche v Commission, (Case C-85/76) EU:C:1979:36. In Hoffman La Roche, the Court of Justice held that exclusive dealing and loyalty rebates constituted by object infringements, save for extraordinary circumstances in which they may be objectively justified.

[4] Intel Corporation v. Commission (Case C-413/14 P) EU:C:2017:632. The Court of Justice articulated the overarching principle that, where a dominant firm submits evidence that its rebates are not anticompetitive, the Commission must carry out an effects-based assessment of dominance, market coverage, the structure, duration and magnitude of the rebates, and any exclusionary strategy vis-à-vis equally efficient competitors.

[5] Intel Corporation v. Commission (Case T-286/09 RENV) EU:T:2022:19 (“2022 Judgment”).

[6] Intel (Case AT.37990), Commission decision of 22 September 2023 (“2023 Decision”). The fine was reduced by approximately 3/8 to account for the fact that five of the eight courses of conduct had been annulled.

[7] Commission v. Intel Corporation (Case C-240/22 P) EU:C:2024:915.

[8] See Article 1(f)-(h) of the 2009 Decision.

[9] See 2025 Judgment, para. 23.

[10] Ibid., paras. 31–32.

[11] Ibid., para. 31.

[12] Ibid., paras. 52–53.

[13] Ibid., paras. 44–45.

[14] Ibid., paras. 59–60.

[15] Ibid., para. 97.

[16] See Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 of 16 December 2002 on the implementation of the rules on competition laid down in Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty (“Regulation No 1/2003”).

[17] See 2025 Judgment, para. 107. The General Court relied on Article 23(3) of the 2003 Regulation No 1/2003, which provides that in fixing the level of the fine “regard shall be had both to the gravity and to the duration of the infringement.”

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid., para. 111.

[20] See ibid., para. 110. See also the 2023 Decision, recitals 59–60.

[21] See 2025 Judgment, para. 113.

[22] Ibid., para. 116.

[23] Commission itself had characterized the number of Acer units concerned as “modest” and that the General Court had similarly found the number of Lenovo units to be “modest”. See ibid., para. 118.